The revolutions of those times took up the historical scene, with the cruelty and generalizations that came with them, destroying the greatness of the intellectual turmoil and dimming the power of thought that lightened the era.

FROM FILANGERI TO THE AMERICAN CONSTITUTION

Behind such revolutions was the need to establish a new status for the individuals and for the population, after centuries of obscurantism; the principles of democracy, forgotten since the time of Athens, came back to life in the passionate discussions of philosophers, legal experts and knowledgeable citizens.

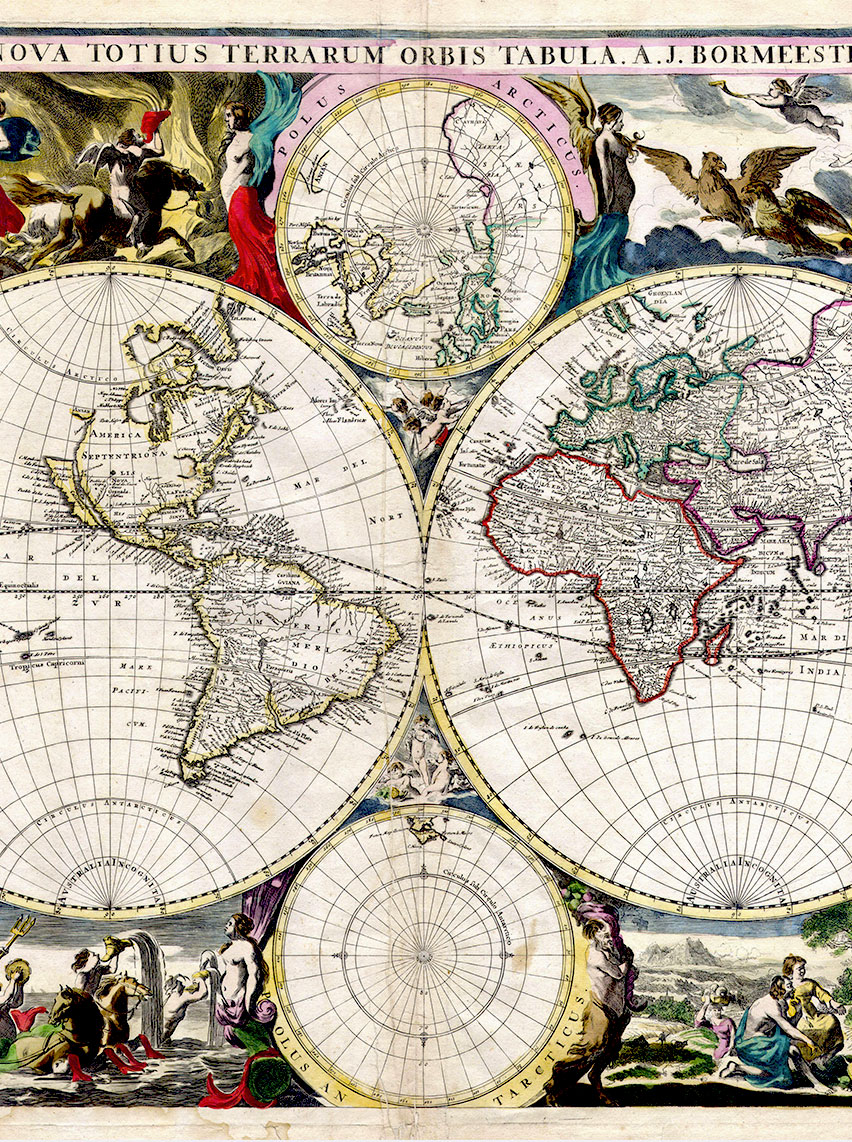

All the interconnections of the European intellectuals were working to contribute to these new ideals, but soon they realized that Europe was not the right continent to apply these ideals, due to monarchical resistance and the persistence of feudalism.

On the contrary, the 13 ex-colonies of North America, the New Nation, were the perfect place to experiment with these new ideals, a sort of world laboratory for modernity.

When reading the works of authors of that time it is possible to grasp not only the actual content, but a surplus of enthusiasm and a universal idealism that went beyond the tight borders and the barriers of the single States, in order to face the entire world and the whole of humanity.

Francesco Mario Pagano, Neapolitan jurist and intellectual, believed that “State and citizenship” were words to abolish from the vocabulary of a modern society.

Antonio Genovesi elaborated the principles of “public happiness” in his economy lectures at the University of Naples.

Gaetano Filangieri in Naples had already published the first two volumes of his treaty on the “science of legislation” in 1780, trying to consider rules that could work for the whole world, outlining the road to grant freedom of the individual and development of the human being.

The visionary power of Filangieri is still appreciated, declining some of the aspects he elaborated: abolition of excise duties to guarantee development; freedom of the press to enable a righteous formation of the public opinion; the right to a fair trial are only few of the colors with which the young Filangieri from Naples tried to depict the rules for a new humanity.

And he was not alone.

The intellectual Masonic net of the times, before the papal bulls that would claim its illegality, has surely had a leading role in the promotion and divulgation of the new ideals, and determined the encounter of the innovative power of the young Neapolitan philosopher and jurist, Gaetano Filangieri, with an undisputed leader of the birth of the New Nation, the United States of America, Benjamin Franklin, both exponents of the Free Masonry.

Gaetano Filangieri was in Naples between 1780 and 1783, at the court of the King, already followed by a consistent fame among intellectuals thanks to his work, and kept a strong correspondence with many of these.

After taking part in the Committee of Five, held by Thomas Jefferson in 1776, in order to corroborate the New Nation in the European courts, Benjamin Franklin was sent to Paris, at the court of King Louis XVI of France, as the first of the American ambassadors.

From 1779 to 1781 Franklin became Master of the Lodge of the Neuf Soeurs, one of the most important expressions of the French Masonry.

In 1781 Luigi Pio, a young secretary representing the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in Paris and another member of the Masonry, obtained the diplomatic role at the same court, becoming an essential channel between Filangieri and Franklin.

Franklin was astonished by Filangieri’s work, and from that moment a strong correspondence started between them, influencing the liberal principles of the first parliamentary and republican democracy of the planet.

The human and personal differences between Filangieri and Franklin were unbridgeable, yet their destinies travelled parallel from 1781 to 1788, up to the point when Tuberculosis broke Filangieri’s young life; he had yet to turn 35.

Young, idealist and intellectual the first; consummate politician, scientist and entrepreneur the latter, they only shared the fact they were great innovators, able to elaborate theories or inventions without any conformism.

Gaetano Filangieri had idealized Philadelphia and Pennsylvania to the point of seeing it as a land where the ideals of freedom that he supported with such vigor had already found life.

In a letter of the 24th August 1782, Filangieri writes to Franklin: “From childhood, Philadelphia has called for my eyes. I have grown so accustomed to seeing it as a land where I could be happy, that my imagination cannot get rid of this idea”.

Everything had started with a letter dated 11th September 1781 from Luigi Pio to Filangieri, where he explained that Franklin wished to encouraged him to obtain the work “Science of Legislation” as it was to be “more useful in his Nation, terribly lacking in aspects of this topic.”

A rich correspondence that followed in the years, in which Franklin also asked Filangieri for suggestions, as well as opinions on the Constitution of the 13 American States, sending him a copy of the book printed in Philadelphia.

This book is lost, and probably is still in some private library of the heirs of the jurist and philosopher.

The correspondence ended with a letter from the 14th October 1787 that Franklin, now President of the State of Pennsylvania, wrote to Filangieri to tell him of the approval of the American Constitution, adding a freshly printed copy of it.

Together with the news, Franklin asked for nine copies of the third volume on Criminal Legislation, and eight copies for the next publications on the Science of Legislation by Filangieri.

The third volume had also been the subject of a letter from Filangieri to Franklin, who was still in Paris, on the 21st March 1784, in which Filangieri sent a sheet from that book, marked by the letter “V”.

That page, recognizable also thanks to stylistic anomalies, included the proposal to establish that, as the first act of the process, there should be the summons to the accused, that is later found in 1791 in the Sixth Amendment of the US Constitution which provides for the right of the accused to be informed of the accusation.

The tribute sent by Franklin on the 14th October 1787 arrives in Naples on July 1st 1788, by which time tuberculosis had begun to undermine the health of Filangieri, that will pass away after three weeks, on the 21st July 1788 in Vico Equense.

It will be Filangieri’s wife, Charlotte Frendel, to respond to Benjamin Franklin, with a letter sent from Naples September 27, 1778 with which she announced the death of her spouse and followed through with Franklin’s request, thus providing the certainty that those copies of Filangieri’s work arrived at destination.

This story, as I said, describes the visionary power of the legal and philosophical thought of Filangieri, but also tells us about the importance of Naples at that time, when it was the centre of a European and international network of intellectuals who set out to forge the society and to regulate the future and the changes, with an eye to the whole world.

It questions us on how much we still need a network of modern Filangieris and Franklins to take charge of processing new rights and duties of which we all feel the need, with the same universal and reforming vision, thinking about the United States, but not only of America.